My Favourite Things I Wrote Last Year /

My Favourite Things I Wrote in 2025

Alright, time to look back at another year of writing.

I’m not quite sure what to think of this year. Last January feels like it was ages ago – I barely remember any of what happened, and it feels super removed from now. That being said, I probably did the most variety of writing this year that I’ve done in years, because I took an experimental fiction course, which forced me to write fiction. (Under normal circumstances I absolutely never write fiction). By some miracle I also wrote some poems??? (I’d claim not to be a poet again, but I know several people who would murder me for trying). I also wrote more academic essays this year than I have in the entire rest of my degree (some of which I actually liked??) and produced lots of blog posts. It’s probably worth taking the time to see if any of that text was actually worth reading.

In this post, I’m going to go through some of my favourite excerpts I wrote last year. Some of them will be from published work, whereas some might even be from WIP work – as long as I wrote it in 2025 and liked it, it’s fair game.

I wrote a post like this last January as well. You can find it here.

Fiction

Dennis Miller – Unredacted LinkedIn Profile

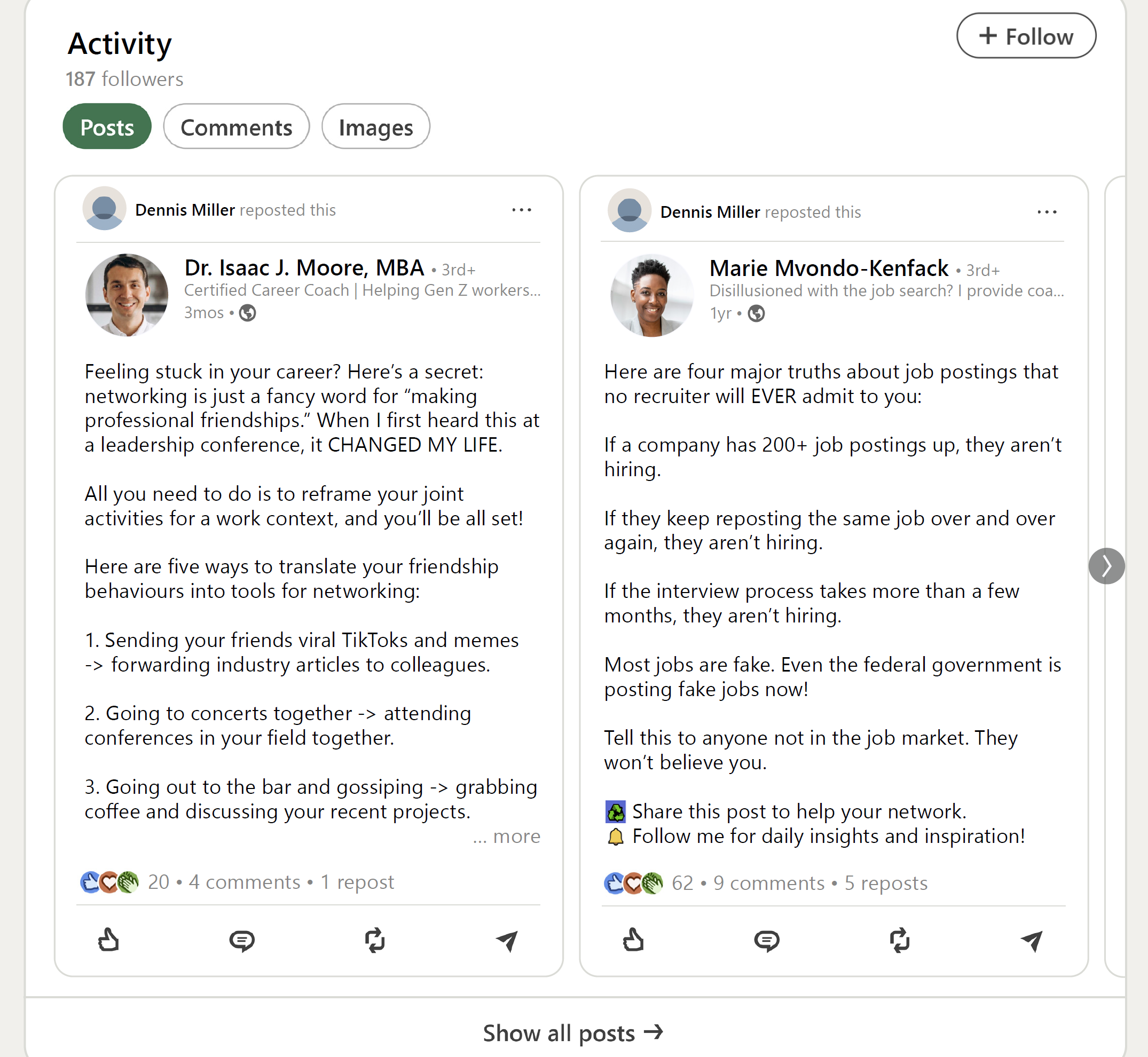

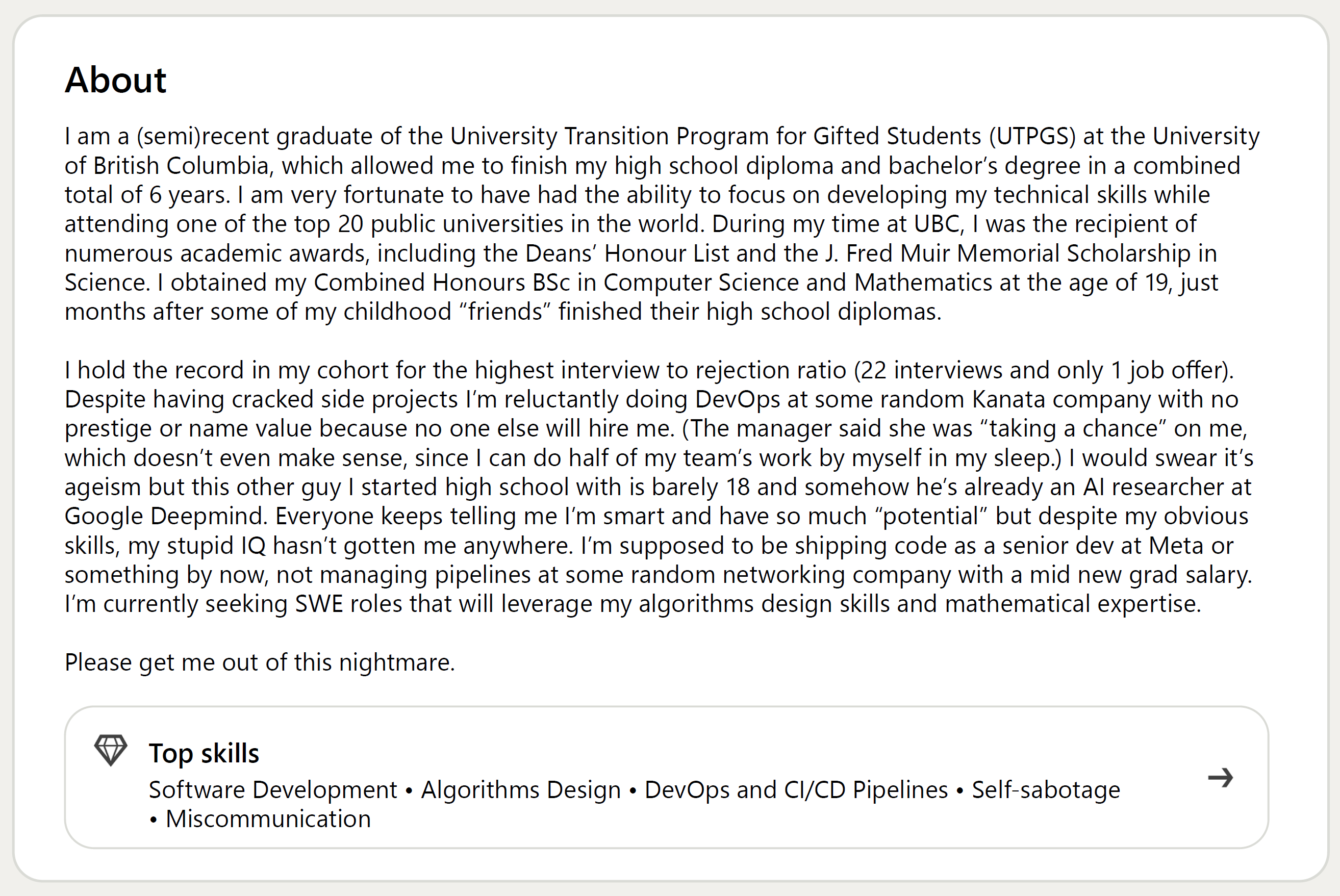

I wrote a piece that was a fictional LinkedIn profile for a disgruntled character named Dennis Miller. He is an underemployed (in his opinion, anyway) CS graduate and his entitlement is through the roof. It’s one of my favourite things I’ve ever created – not only did I get to write these insane sounding LinkedIn sections, I also had fun recreating the entire LinkedIn interface from scratch in InDesign, just so it would look nice and have clean page breaks as a PDF.

It’s really hard to publish this anywhere, because it only hits in PDF form and you basically need to see all of the graphics for any of it to make sense. But boy, was it fun to write.1 I’ll probably put the entire thing up on this blog at some point.

I think Dennis’s story is a worthwhile read, obviously, but my favourite part of the piece is actually the Activity section, which features fake LinkedIn posts I wrote to really sell the illusion of the profile. They were painful to do research for (spending time on the LinkedIn platform makes me want to die), but damn, I do think I hit the LinkedIn influencer slop tone really well…

Seriously, look at the nonsense Dennis has been reposting. He must be a very, very sad man. This certified career coach2 (does he even have any clients?) has both a doctorate and an MBA but he really wants you to know that your meme posting habits can be reframed to help advance your career.

Here’s Dennis’ About section.

Remember, even federal government jobs are fake now.

Poems

I wrote a poem about Elon. I wish I could post it here, but I can’t, because then it will be considered “published”, and then I won’t be able to publish it anywhere else, which is annoying. But here are a few lines of it:

talentless hacks ruin everything. you’re different,

don’t worry. cut your grandma’s social security check

so elon can crash another rocket. these things

don’t apply to us, until they do. erasures start quietly,

until they’re blinding. learn to computer; increase

government efficiency. I sent three hundred and

eighty-seven tweets during work hours and it’s all

bullshit, maybe I should get fired for it.

I like it because it’s so different from what I normally write. It’s full of non sequiturs and borderline nonsensical, but it has its moments of wisdom. Usually I don’t write poems like this – instead, I typically write very long, logical narrative poems that barely even register as poems to me (the other poems I wrote this year were that kind). But this poem format felt correct for some reason… I think the world is just starting to feel more and more like a collection of insane non-sequiturs, especially in the US…

Essays

I took some English literature courses this year, which meant that I was forced to write some academic essays for the first time in a few years. Overall, I think the essays were not that great, but I think some of the ideas I had were pretty interesting, so that was cool. For example, I wrote an essay called “Eve Re-Enters the Garden of Eden: Perrault’s ‘Blue Beard’ and the Politics of Marriage”, which has to be one of my favourite essay titles I’ve written.

Immersive Documentary Class Essay

I took a seminar on “immersive documentary”3 over the summer, where we read all kinds of dark texts about war and murder and genocide and watched some pretty dark documentaries as well. For my final research essay, I compared two documentaries about political fugitives – Underground (1976) and CITIZENFOUR (2014)4 – and tried to see whether there were any similarities between them. I ended up coming up with some kind of conjecture about narrative control being both shared and disputed by the documentarians and film subjects… which I was never able to fully explore because the entire essay was written in the six hours before it was due (please do not try this at home). It wasn’t a very good or polished essay, but I do quite like the opening paragraphs, which attempt to introduce and describe why Underground is such an uncomfortable film to watch.

One of the most bizarre and disturbing films I have ever watched is a 1976 documentary called Underground. In it, the directors Emile de Antonio, Mary Lampson, and Haskell Wexler spend three days in a safehouse filming and interviewing members of the Weather Underground Organization, a left-wing militant group that went into hiding after declaring war on the U.S. government in 1970. The Weather Underground believed in overthrowing U.S. imperialism and are famous for a series of actions they referred to as “armed propaganda,” which involved symbolically bombing political targets such as the Capitol, the Pentagon, and the Department of State. If you’ve never watched Underground, you should learn a bit about the Vietnam War period, watch the film, and then never watch it again. I know the film is important for historical reasons, but I can’t bring myself to watch it in full a second time. It’s not scary in the same way that a thriller or a horror film is scary, but the atmosphere is dark and gloomy. The lighting is terrible. A few scenes are shot with two dark silhouettes facing a blanket that reads “[t]he future will be what we the people struggle to make it.” Others are shot through a scrim, a thin piece of black fabric that lets enough light through for you to be able to see that there are people on the other side, but not enough to see any details (I find these the most disturbing). Others still are shot in such a way that the filmmakers’ faces are visible, but the members of the Weather Underground have their backs to the camera. You never see the Weatherpeople’s faces, which makes the film feel impersonal and distant.

Underground is notable for a variety of reasons, the main one being that the U.S. Government did not want it to exist. An article published in 1976 refers to the film as “the latest joke on the FBI;” it also includes a statement in which a congressman refers to the directors of the film as “a group of Hollywood’s left-wing crackpots” and to the film as a “propaganda puff piece”. Over the roughly 6-year period during which members of the Weather Underground were in hiding, the FBI committed numerous resources to trying to find them and largely failed. In 1975, the government caught wind that de Antonio, Lampson, and Wexler were making a film with the Underground and served them with subpoenas ordering them to bring their footage before a Federal Grand Jury, presumably hoping to find information on the fugitives’ location. Fearing that their footage would be confiscated, the filmmakers refused to cooperate, and the subpoena was withdrawn after outrage from the Hollywood community. Everyone involved in the film knew this might happen, which is why it was shot in such a way that none of the fugitives could be identifiable.

Munro Beattie Lecture Retrospective (WIP)

Another essay that I started but never finished had to do with my thoughts after attending the 2025 Munro Beattie Lecture, which was given by Ann-Marie Macdonald. Apparently she is a very famous writer who has won a bunch of awards, and the lecture hall was full of people who were fans of her work. I was not aware of this; in fact, I didn’t even know who she was before I walked in.

That entire night, from the lecture itself to the book signing, were a deeply weird experience. MacDonald is a very flamboyant speaker who has some very interesting ideas about how to be a writer, a lot of which I disagree with, and I think I probably spent more time trying to understand how I felt about my reactions to what she was saying than actually thinking about what she was saying.5 The fact that it seemed like everyone else already knew her work was also a crude reminder that I was a CS major in a lecture hall full of people studying English literature (which I technically minored in but know pretty much nothing about). I have never felt so illiterate and uncultured in my life.

Here is an excerpt:

Ann-Marie’s talk is making me think about my relationship with writing advice. She is saying so many beautiful things that I disagree with, giving a perspective on storytelling that is quite orthogonal to my own, and I am noticing, internally, as I disagree with her in real-time. Her work is the epitome of “show, don’t tell”, it seems, and I have quite a good relationship with telling. Her work, her approach is very visual, and I am not a very visual person. I am artistically mature enough that it doesn’t bother me but not artistically mature enough to not have to tell myself it doesn’t. I am thinking about how a few years ago, I might have interpreted a professional’s differing perspective as a reason to feel insecure about my own work. I am thinking about how I’ve gotten work published before, so I can’t be doing everything wrong. I am thinking about how maturing as a writer means feeling less influenced by the differing opinions of other writers. I am thinking about how I have a fuzzy relationship with the word “story” and thinking that maybe it comes from the fact that I write CNF. Ann-Marie is talking about where stories come from, and I am thinking about my own story.

And here is a second, longer, excerpt:

A while after the end of the talk, I approach Ann-Marie, as many others have, for a book signing. I have spent so long debating what I will or will not say that most of the audience has left and there is almost no signing line to speak of. I have never heard of her before this talk, but I now understand that she is Famous, that amongst this crowd of lifelong students of literature, her name and her words carry weight. I am uncharacteristically shy; I have never felt so tongue-tied at the idea of interacting with a speaker before.

As she opens my book – a copy of Adult Onset, a book I have never heard of before today and likely would never have thought to read otherwise – I comment on her pen. It is a Pilot VPen, a disposable fountain pen with blue ink and a medium nib. I collect fountain pens, I tell her. She tells me she’s using it because it’s a special occasion. She asks if the book being signed is for me; I acquiesce and spell out my name. She asks me whether I am a writer. I tell her I am.

I tell her I have a question. It’s about branding, I say. How does she feel about it? How does she reconcile the joy she’s felt at living between all of her different careers with today’s expectation that young people brand themselves and specialize and market only one version of themselves? It’s a question that’s been burning in me since the end of the talk, but it feels private somehow, a question I wasn’t willing to ask in the church hall-turned auditorium. It’s hard, she tells me. It’s difficult for youth now. But she feels like her entire career has been about storytelling, and so in some sense, she’s only ever been doing one thing.

I tell her I also study computer science, that I find it difficult to reconcile loving writing with loving technology. That it feels weird and alien to continue living in both worlds, that it always feels like there is external pressure for me to choose. She tells me I shouldn’t choose, that I don’t have to choose. That there is always space for me to do both. That I should pursue all of my interests to the fullest.

The common point is you, she says. Somehow, the answer feels thin.

I don’t think I’m ever going to finish this essay, but I do like the parts that exist.

Blog Posts

You Need to Be Proactive [link]

This is, by far, my favourite post on the blog, and I think it’s probably the most important bit of life advice I have to offer, so I end up sending it to a lot of people. I try really hard to live by the notion that one should be proactive about solving their own problems and that they should be on top of reminding people when they need something from them.

Honestly, I have a lot of things to do – too many, even. If you ask me for something, and I tell you to remind me to do it, it is, in some sense, a coarse filter to see how important it is to you. If I explicitly ask you for a reminder and you don’t give me one, I’m going to assume whatever you asked for isn’t that important to you and I may or may not actually do it. Is this a fair way for me to behave? Probably not. But then again, life isn’t fair.

Here’s the first paragraph of the blog post.

One of the things that has been repeatedly drilled into me over the past year or so is the fact that if you want people to do things for you, you’re most likely going to have to harass them. (I don’t mean literal harassment, by the way – please don’t commit a criminal offense and say I encouraged you.) This is true especially when working with highly busy people like managers and professors. If you want something, you can’t just assume they’ll intuit that and give it to you – you have to ask (and assume they’ll forget, then ask them again). If you need them to do something for you, you’ll need to remind them, and inform them of the deadline, likely multiple times. Everyone has their own problems to worry about and the thing you need might not be top of mind. The burden of remembering is on you.

30-Minute Meetings Are a Scam [link]

In this post I argue that scheduling half-hour meetings sucks, since they inevitably end up taking more like 15 or 45 minutes. I also argue that we should be less scared of blocking out a full hour for a meeting.6 Just read the post, it’s short.

Oh, and here’s a fun bit:

Here’s one fun heuristic I learned from one of my colleagues: if you’re ever in a meeting that feels pointless to you and you’re not even sure why you’re there, figure out how much money each person is making for the duration of that meeting. That’s the cost of this meeting. Now, sum up the amount of money being made by everyone who doesn’t need to be there. That’s the amount of money being wasted by this meeting.

Getting to the End of the Thought; or, Why Write in the Age of AI? [link]

Everyone feels the need to comment on AI these days and I am no exception. This post is my contribution to that conversation, albeit from the point of view of a writer – I’m trying to argue that the real value in writing anything isn’t just in having a written product, but also in building your ability to clarify and dissect your own thoughts.

While writing can also function in the exploratory modes I just described above, as far as I’m concerned, what the written mode uniquely excels at is focused investigation of a single idea, or what I’m going to call “getting to the end of the thought”. It can be useful to wander around the edges of an idea or opinion to see its contours and different ways to approach it, but that’s not always enough. When clarity and precision are at stake, when I want to figure out exactly what it is that I think and why it is that I think it, it is imperative for me to write things down. Getting to the end of a thought involves following an idea as far as it’ll take me and seeing what emerges, and I need somewhere to put all of the thoughts I’ll gradually dig out of my brain on the way there. Only then can I sift through the materials and figure out what the core of my actual argument is; only then can I construct a conclusion. This takes time, focus, and trial and error, and I find it’s almost impossible to do without writing. At the end of the process, it feels like I’ve unknotted some pathways in my brain, like I’ve untangled some deep knot of confusion and come out of the other side with understanding.

This, more than any other reason, is why I bother to write anything at all. A lot of corporate communications feel pointless, and a lot of the academic writing done in courses feels stilted, forced, and transactional to me, more about proving that one can go through the motions of explaining and arguing something than about actually presenting any ideas of value. I think lots of people have gotten the idea that writing texts is always like this, that it’s always some kind of bullshit generation exercise where you make a product no one will read or care about. It can be, and if your objective is to create bland corporate texts, I can understand why you may want to delegate your tasks to a machine. But I think it’s dangerous to conflate learning to write with learning to generate bullshit content. The skills you gain by learning to communicate cannot be replaced by a machine.

I Am Slowly Discovering That I Have No Idea How to Read [link]

I think the main thing I learned in my fourth year courses was how to read. I spend a lot of time reading nonfiction and fiction books, so I thought I was pretty good at reading, but boy, was I wrong. Reading academic texts is a whole different skillset, and my first few attempts at it were painful. The first time I tried to read a math paper, I tried my best to stumble through the introduction and looked up after two hours to find that I’d only read two pages. A sketchy reading of a “short” and relatively “simple” to understand network security paper takes me about an hour, and by the end of that I have more questions than answers. I feel like I’ve had to develop a whole new set of mental muscles to deal with these papers.

A lot of reddit posts I’ve read online seem to suggest that as you move further in your education, you will have so many things to read that you will speed up your reading and figure out how to strategically skim for information. However, for whatever reason, I have not found that to be true for me at all. I’ve been slowing down my reading, not speeding up. These days, I try to read with a lot of care and active attention – I highlight things, scribble questions in the margins, try to track down references, and so on. I don’t feel comfortable claiming to have read an academic paper unless I’ve physically read every word of it, and even then, I usually still don’t understand it. Maybe eventually I’ll start to feel differently about it, but for now, I think this kind of literacy is excruciatingly difficult and painful.

When I read for my essay writing course, I struggle to figure out how I should be approaching the text and the theory texts we use for analysis. I’m not sure how I’m supposed to be “getting under the surface of the text” or coming up with ideas on what to analyze. I feel like I’m supposed to be pulling from so much historical and cultural context and theoretical knowledge that I simply do not have. I’m not sure how to read or interpret the theories or apply them to the story. I’m not sure if I’m supposed to be constructing a lens that I impose onto the story or if I’m supposed to be putting the story into a conversation with other ideas. A while ago I went down an internet rabbit hole where I tried to learn about “close reading” because I felt like I didn’t know a good way to engage with literature and pull out ideas and conclusions.

This is what I mean when I say I feel like I have no idea how to read. I think way too many people write off humanities majors as not actually learning anything, but this is the type of reading they do day in and day out, and as a typical STEM major, I can’t do it. It is slow, and it is painful, and it is a skill I wish I’d been formally taught how to do. Trying to learn how to do literary analysis is giving me the same kind of pain and confusion as I first had when trying to decipher mathematical research papers. I have never understood the idea of humanities degrees teaching you transferable skills as much as I am now while trying to get through this massive volume of texts. (Whether or not the specific skill of literary analysis is actually useful outside of academic contexts is another discussion, however.)

I’m Still Not Entirely Sure What a “Poem” Is [link]

An essay about why I usually feel very uncomfortable whenever someone calls me a “poet” (I definitely do not feel like one).

First excerpt:

Part of the self-consciousness, I’ve decided, comes from the lens with which I approach things. I care about big picture ideas and weaving bigger throughlines. A lot of my essays, I find, have a sense of distance within them that’s measured in years. I’ll be like, I had this idea, or this experience, several years ago, and in hindsight I think this is what it meant, and as of right now this is how I feel. Poems are not like this. I paint in sweeping, large brushstrokes, and poems, I find, use tiny ones. I think so many poems work at a microscale and evoke larger thoughts through juxtaposition. Notice this thing. Notice this unrelated thing. Notice this tangentially related thing. Here is some description with carefully chosen words that will evoke this other idea. When I write metaphors, they’re to explain an idea. In so many poems, the metaphor is the idea. I guess these differences probably sound minute but to me they matter. They’re the beginning of me trying to unravel why I find poetry so difficult.

Second excerpt:

When I attempt to write poems, I usually realize they’re actually essays. I haven’t figured out how to have ideas that feel small yet. I haven’t mastered the art of writing microlayers the reader needs to unpeel and I don’t know if I want to. I think this is at the core of my anxiety. It’s this feeling of wanting to paint with large, sweeping brushstrokes in the land of small canvases and tiny brushes.

What Makes a Graduate-Level Course Different From a Senior Undergraduate Course? [link]

I think a lot about educational philosophy, and sometimes that results in a 7000 word article about minute differences between upper-level course types.

I think the first time the difference between being in a grad level course and an undergrad level course really hit me was when I went into my prof’s office to ask for help with my final project. I think I asked him what the relationship between the two different definitions of a submodular function were, and he said he had no idea and would probably have to look it up. Then he moved on, and we never talked about it again, at which point I understood that learning the required background for my course project was mostly going to be my problem and that I was going to have to find some other way to learn it.

At the undergrad level, I think profs tend to steer students towards topics they know a lot about and have already seen before, and therefore are able to provide a lot more guidance to students who are struggling and need help. In fact, some courses require all students to do exactly the same project or write their report on the same topic, whereas in a grad course you’re pushed to choose something that is interesting and relevant to you, so long as it’s at least tangentially related to the course content. What I did not realize was that at this level, you’re starting to get specific enough that “tangentially related” might already be far outside of your professor’s area of expertise. At that point, you’re on your own.

-

It also let me work out my feelings of frustration towards my peers, which were considerable in their depth. This piece really says a lot about how I feel about undergrad CS major culture, and especially about the people who act like this. They drive me insane. ↩︎

-

In case you’re double-checking, yes, he is made up! None of the people mentioned in this piece are real. Though some of them may be composites of multiple annoying people I’ve met IRL… ↩︎

-

You know, whatever that means – seriously, the entire course was about trying to define that terminology in some abstract sense. I can’t tell whether I love or I hate that we did this. ↩︎

-

Yes, this is the documentary about Edward Snowden. ↩︎

-

On this note, in my notes, the subtitle of this essay is “I started out trying to write a review of the lecture but instead wrote an essay that’s 100% about me.” ↩︎

-

Fine, I’ll admit that one benefit of half-hour meetings is that you can book about twice as many of them as you can hour-long meetings, and that you probably don’t actually want to book back-to-back 15 minute meetings, so half an hour might be a good compromise. ↩︎